Article by Michael Beckerman

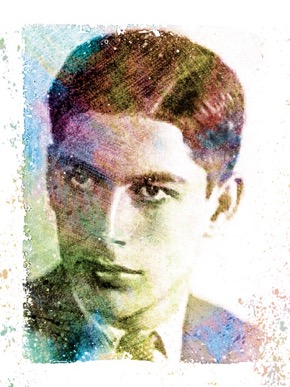

Gideon Klein (1919-1945) was a pianist, composer, writer and educator. In his short life he combined a dizzying array of skills, experiences, musical styles and activity. He arranged Hebrew folk melodies, wrote quarter-tone compositions, served as repetiteur for the infamous production of the Verdi Requiem in Terezín, and was a formidable presence in the musical life of that place.

Michael Flach, who was in Terezín with Klein, created a poetic impression of his presence in this excerpt from “A Concert in the Old School Loft (played by Gideon Klein)”

“And yesterday that man cut all the veins He opened all the organ pipes He bribed all birds to make them sing To make them sing Even though the verger’s hard fingers harshly sleep on top of us”

Life

Klein was born in the Moravian town of Přerov in 1919, the youngest of four children. His parents were Czech-speaking Jews and he grew up in a traditional atmosphere. His gifts showed early, and at age 11 he began piano lessons with Růžena Kurzová in Prague; by the time he was twenty he had moved permanently to the city. He began composing in 1934, and continued studying piano with Vilém Kurz. He completed his Master Class in 1939 and continued studying musicology at Charles University and composition with Alois Hába.

These studies took place in difficult and uncertain conditions — by November of 1939 the Czech universities were closed by the Nazis, and Klein was forced to leave the Conservatory by 1940. An attempt to study in London in response to an invitation to study at the Royal Academy of Music was aborted. For the next year Klein tried to continue his activities using the pseudonym Karel Vránek, playing concerts in private homes, and continuing to work as a composer. His own apartment became the site of something very much like a salon, a meeting place for musicians and writers. On December 4th 1941 he was sent to Terezín where he remained for almost three years.

Klein’s time in Terezín is a record of remarkable activity under adverse circumstances. He became an avid educator, on musical and other subjects, and devoted himself to the teaching of the camp’s orphans. He remained active as a performer, serving as pianist for several opera productions and playing in solo recitals such works as Beethoven’s Op.110, Janáček’s Sonata, and Busoni’s transcription of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in C Major and performing such chamber compositions as the Schubert Trio in Bb, Op.99, and piano quartets by Brahms and Dvořák. He also displayed conspicuous artistic growth as a composer, completing several choral works, a formidable Piano Sonata, a Fantasy and Fugue for String Quartet, and his final work, a Trio for strings, completed a week or so before he was transported to Auschwitz.

Like so many others, his final days, spent at the Fürstengrube concentration camp, are impossible to document. One of the last sightings of Klein is described in Milan Slavický’s excellent biography of the composer. According to a prisoner named Hans Schimmeling, all new arrivals at Fürstengrube were subject to a doctor’s examination. They were forced to wait naked in a room together, guarded by an SS officer. There happened to be a piano in the room, and the SS man asked if anyone played the piano. “The eyewitness was not a musician and did not recognize the piece, yet to this day he remembers Klein’s playing and is convinced that had Klein played something to the guard’s liking (a waltz, a ditty or something of that kind), he could have alleviated his fate and perhaps even saved his life.”

Klein’s legacy was preserved by several musicians, and carried forward primarily by his sister, the remarkable Eliška Kleinová who took great pains to make his music available and encourage a range of performers to take an interest in it. In her goals, and hopefully in her successes she embodies many of the same intentions of the Orel Foundation.

Although there was a flurry of interest in Klein’s music immediately after the war, his legacy and that of his fellow Terezín prisoners did not fare so well under the Communists. Complex conflicts and geo-political alliances created an atmosphere of de facto anti-Semitism in Czechoslovakia under normalization, ranging from the Slánský trials to the more benign but similarly toxic undermining of both religious and cultural forms.

Works

In his short and eventful life Gideon Klein completed approximately twenty-five original works and ten or so arrangements of songs, mostly in Terezín. Milan Slavický divides the composer’s oeuvre into three periods. From 1929-38 we have the development of a self-taught composer, and works ranging from first attempts to more assured utterances. From 1939-41 Klein became more professional since he was attending Alois Hába’s composition class at the Prague Conservatory. It was at this time he experimented with quarter-tone music. The third and most significant period took place while the composer was in Terezín and combined a far-reaching modernity with the quite natural desire to speak to a large audience about the circumstances in which he found himself. It is this latter music that has been most performed.

Until 1990 it was assumed that most of Klein’s youthful compositions had disappeared during the war years. In the words of Milan Slavický “one of Gideon Klein’s friends found a suitcase that had remained unopened since the war—and in this suitcase were almost all Klein’s compositions from the period preceding Terezín. Gideon Klein gave this suitcase to his friend shortly before joining the transport for Terezín…In this respect the newly discovered works reveal Gideon Klein as an experimenting composer of lofty ambitions, in harmony with the most advanced endeavors, thus substantially modifying his image.”

Klein’s compositions are distinguished by a clarity of form, an ongoing interest in contemporary movements such as jazz, neoclassicism, serialism and microtonalism and an abiding interest in contrapuntal design and variation technique. He was also profoundly influenced by his career as a performer, and his exploration of Busoni’s Bach arrangements created a warm synthesis of Bachian intellectual goals and a kind of hyper-expressivity.

Recent Comments