THERESIENSTADT CONCENTRATION CAMP

The city of Terezin, which was located in Czechoslovakia, received its name from Maria Theresa, the mother of the emperor reigned between 1740-1780, was invaded by the Nazis on June 10th, 1940 during the second world war. The Theresienstadt concentration camp that would be filled with hundreds of, thousands of artists was established by the Nazis on 24th of November 1941. Thousands of Jews lost their lives in Theresienstadt due to extremely harsh living conditions. More than 50.000 Jews had been sent to the camp which was only for 7000 people, and because of this reason life conditions severely worsened and many Jews lost their lives because of insufficient food. Taking medication was strictly prohibited and the punishment for that was either heavy labor or death. Even in these harsh circumstances some of the artists managed to survive and continued to create with the power of creation.

Composers of Terezin

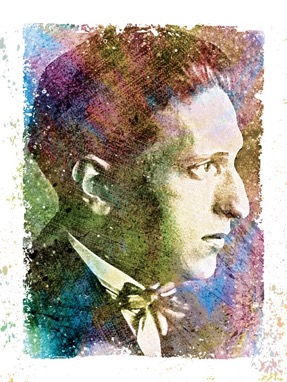

Pavel Haas

Article by Michael Beckerman

Pavel Haas was born into a wealthy and prominent Jewish family in the Moravian capital of Brno. This was a city with a rich cultural life, and it was during Haas’ childhood that Leoš Janáček established himself as a leading figure, both regionally and nationally. Haas became an important composer of theater and film music, composing music, for example, for Karel Ĉapek’s infamous RUR (Rossum’s Universal Robots). During this period he worked several times with his brother, Hugo Haas, who became a successful actor in the United States after the war. The war years severely limited Haas’ professional development, and in 1941 he was sent to Terezín. Although at first he was too ill and depressed to compose, he later became part of the rich musical life of the camp, writing several works that are considered classics of that time. He was deported to Auschwitz in mid-October 1944 and immediately killed.

Life

A compositional prodigy, Haas studied at the school of the Philharmonic in Brno until he was drafted into the Austrian army in 1917. He remained in Brno during that time, and in 1919 he began the serious study of composition at the Brno conservatory, working with Jan Kunc and Vilém Petrželka. Later (1920-22) he became a part of the master class of the conservatory led by Leoš Janáček. As one of the only cultural figures in Moravia to have achieved international success, it is impossible to overestimate Janáček’s stature or his influence in Brno and Moravia more broadly. Although Haas clearly went in his own direction, Leoš Janáček’s effect was profound.

Starting in his early 20’s, Haas was a prolific and versatile

composer who drew on the leading trends of the time. The 1930’s was a

great age of Czech cinema, and one of its leading figures was Haas’

brother Hugo. During this period Pavel Haas wrote several notable

scores for both stage and film, and reached his maturity as a composer

in the mid-1930’s with such works as the opera The Charlatan, String

Quartets 2 and 3, and the Suite for Oboe. A major work from this

period, a large symphony, was left unfinished and completed only after

Haas’ death.

When Czech society began to break down under the

pressure of the Nazi presence, Haas, like other Jewish composers, took

whatever steps he could to protect his interests. In this case, this

included divorcing his wife in order to shield her from anti-Semitic

policies. Haas was deported to Terezín in 1941.

Reports of Haas’ life in Terezín usually include the information that Haas was ill and depressed upon his arrival and only returned to some kind of creative productivity when the energetic and intrepid Gideon Klein put several sheets of blank music paper in front of him and urged him to return to his work. While in Terezín, Haas wrote several works including, most notably, theStudy for Strings, immortalized in a clip from the 1944 Nazi propaganda film created to show the camp as a kind of idyllic spa for Jews. Here we see the composer sitting nervously and finally taking several stiff bows. Conducted by Karel Ančerl in the film, this work was successfully revived after the war. Among his greatest works, composed during his last year in Terezín, are theFour Songs on Chinese Poetry. A mature composition, written on many different levels, the cycle was performed in a concert in June of 1944.

It was likely clear to any of the more highly placed prisoners that, as soon as the Red Cross visit and the propaganda film had been completed, there would be no reason to protect any of the long-term internees. By the end of the summer things had begun to change, and huge transports started at the end of September 1944. On October 16th, Haas was placed in a transport with other Terezín composers Klein, Krása, Ullmann, and Karel Ancerl. According to Ančerl’s testimony, Haas, along with Ullmann and Krása, was immediately gassed.

Works

From his earliest period, Haas showed an equal affinity for abstract

music and music based on text. The most formative influence on his

music was the compositional legacy of Leoš Janáček. Janáček’s dramatic

intensity played a role in Haas’ artistic development, but also his use

of short motives and his use of Moravian musical elements. Haas also

had an affinity with Hebrew chant and incorporated these along with

neoclassic and jazz idioms.

This integration of Janáček’s style with

his own mature voice can be heard most notably in such works as the

1938 Suite for piano, in the String Quartet #3, with its synthesis of

local and international musical elements, in the Suite for Oboe and

Pianofrom 1939, and of course in the great dramatic work of his

maturity, The Charlatan. Here we have a compelling combination of

surface and depth, immediate charm and subtlety. These elements also

seem to have been present in a powerful blend in Haas’ incomplete

symphony, posthumously completed. For example, in the final variations

movement of the 3rd quartet we have Beethovenian depth, Janácek’s

aphoristic approach, Moravian rhythms and references to Jewish folk

tunes.

This deepening of Haas’ approach continued while the composer was in Terezín, reaching its apotheosis in the Four Songs on Chinese Poetry. Here there is a kind of ideal, if agonizing and tragic, synthesis. These songs of love and longing for home seem to capture the mood of Terezín as much as any other compositions. Set as a series of interior monologues, and making periodic reference to such things as the Czech historical chorale “St. Wenceslaus,” the cycle offers us an affective world poised between life and death, between affirmation and complete despair.

Haas seems to have a kind of personal relationship with the “St. Wenceslaus” melody, a tune used literally hundreds of time by composers in the Czech Lands over the centuries. It is present in the incomplete symphony, and used several times in the Suite for Oboe and Piano. The songs from Chinese Poetry also refer to it, obliquely in an especially poignant way.

©2015 The OREL Foundation

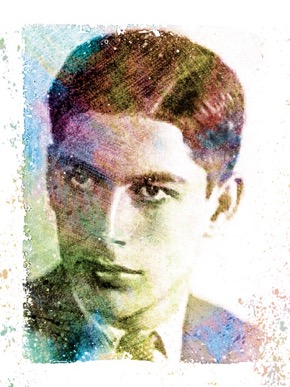

Gideon Klein

Article by Michael Beckerman

Gideon Klein (1919-1945) was a pianist, composer, writer and educator. In his short life he combined a dizzying array of skills, experiences, musical styles and activity. He arranged Hebrew folk melodies, wrote quarter-tone compositions, served as repetiteur for the infamous production of the Verdi Requiem in Terezín, and was a formidable presence in the musical life of that place.

Michael Flach, who was in Terezín with Klein, created a poetic

impression of his presence in this excerpt from “A Concert in the Old

School Loft (played by Gideon Klein)”

“And yesterday that man cut

all the veins He opened all the organ pipes He bribed all birds to make

them sing To make them sing Even though the verger’s hard fingers

harshly sleep on top of us”

Life

Klein was born in the Moravian town of Přerov in 1919, the youngest of four children. His parents were Czech-speaking Jews and he grew up in a traditional atmosphere. His gifts showed early, and at age 11 he began piano lessons with Růžena Kurzová in Prague; by the time he was twenty he had moved permanently to the city. He began composing in 1934, and continued studying piano with Vilém Kurz. He completed his Master Class in 1939 and continued studying musicology at Charles University and composition with Alois Hába.

These studies took place in difficult and uncertain conditions — by November of 1939 the Czech universities were closed by the Nazis, and Klein was forced to leave the Conservatory by 1940. An attempt to study in London in response to an invitation to study at the Royal Academy of Music was aborted. For the next year Klein tried to continue his activities using the pseudonym Karel Vránek, playing concerts in private homes, and continuing to work as a composer. His own apartment became the site of something very much like a salon, a meeting place for musicians and writers. On December 4th 1941 he was sent to Terezín where he remained for almost three years.

Klein’s time in Terezín is a record of remarkable activity under

adverse circumstances. He became an avid educator, on musical and other

subjects, and devoted himself to the teaching of the camp’s orphans. He

remained active as a performer, serving as pianist for several opera

productions and playing in solo recitals such works as Beethoven’s

Op.110, Janáček’s Sonata, and Busoni’s transcription of Bach’s Toccata

and Fugue in C Major and performing such chamber compositions as the

Schubert Trio in Bb, Op.99, and piano quartets by Brahms and Dvořák. He

also displayed conspicuous artistic growth as a composer, completing

several choral works, a formidable Piano Sonata, a Fantasy and Fugue for

String Quartet, and his final work, a Trio for strings, completed a

week or so before he was transported to Auschwitz.

Like so many

others, his final days, spent at the Fürstengrube concentration camp,

are impossible to document. One of the last sightings of Klein is

described in Milan Slavický’s excellent biography of the composer.

According to a prisoner named Hans Schimmeling, all new arrivals at

Fürstengrube were subject to a doctor’s examination. They were forced to

wait naked in a room together, guarded by an SS officer. There happened

to be a piano in the room, and the SS man asked if anyone played the

piano. “The eyewitness was not a musician and did not recognize the

piece, yet to this day he remembers Klein’s playing and is convinced

that had Klein played something to the guard’s liking (a waltz, a ditty

or something of that kind), he could have alleviated his fate and

perhaps even saved his life.”

Klein’s legacy was preserved by several musicians, and carried

forward primarily by his sister, the remarkable Eliška Kleinová who took

great pains to make his music available and encourage a range of

performers to take an interest in it. In her goals, and hopefully in her

successes she embodies many of the same intentions of the Orel

Foundation.

Although there was a flurry of interest in Klein’s music

immediately after the war, his legacy and that of his fellow Terezín

prisoners did not fare so well under the Communists. Complex conflicts

and geo-political alliances created an atmosphere of de facto

anti-Semitism in Czechoslovakia under normalization, ranging from the

Slánský trials to the more benign but similarly toxic undermining of

both religious and cultural forms.

Works

In his short and eventful life Gideon Klein completed approximately

twenty-five original works and ten or so arrangements of songs, mostly

in Terezín. Milan Slavický divides the composer’s oeuvre into three

periods. From 1929-38 we have the development of a self-taught composer,

and works ranging from first attempts to more assured utterances. From

1939-41 Klein became more professional since he was attending Alois

Hába’s composition class at the Prague Conservatory. It was at this time

he experimented with quarter-tone music. The third and most significant

period took place while the composer was in Terezín and combined a

far-reaching modernity with the quite natural desire to speak to a large

audience about the circumstances in which he found himself. It is this

latter music that has been most performed.

Until 1990 it was assumed

that most of Klein’s youthful compositions had disappeared during the

war years. In the words of Milan Slavický “one of Gideon Klein’s friends

found a suitcase that had remained unopened since the war—and in this

suitcase were almost all Klein’s compositions from the period preceding

Terezín. Gideon Klein gave this suitcase to his friend shortly before

joining the transport for Terezín…In this respect the newly discovered

works reveal Gideon Klein as an experimenting composer of lofty

ambitions, in harmony with the most advanced endeavors, thus

substantially modifying his image.”

Klein’s compositions are distinguished by a clarity of form, an ongoing interest in contemporary movements such as jazz, neoclassicism, serialism and microtonalism and an abiding interest in contrapuntal design and variation technique. He was also profoundly influenced by his career as a performer, and his exploration of Busoni’s Bach arrangements created a warm synthesis of Bachian intellectual goals and a kind of hyper-expressivity.

Viktor Ullmann

Article by Gwyneth Bravo

Viktor Ullmann (1898–1944) was born on 1 January 1898 in the garrison town of Teschen in Silesia, in what belonged to the Austro–Hungarian Empire and is now a part of the Czech Republic. Educated in Vienna, Ullmann made important contributions to both Czech and German cultural life as a composer, conductor, pianist and music critic. Shaped by his engagement with Schoenberg’s musical philosophy, German aesthetics, as well the anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner, Ullmann understood the role of art as central to human spiritual and ethical development. Prior to his death in 1944, he wrote that “[artistic] form” must be understood from the perspective of Goethe and Schiller as that which “overcomes matter or substance [and where] the secret of every work of art is the annihilation of matter through form—something that can possibly be seen as the overall mission of the human being, not only the aesthetic but ethical human being as well.” Within the context of his own compositions, Ullmann used form as a powerful commentary on his own self–conscious engagement with the traditions of Western art music as he engaged with them in the works of Schoenberg, Mahler and Berg.

Childhood and Youth 1898–1919

The son of Maximilian and Malwine Ullmann, Viktor Ullmann’s birth was registered with the Catholic community in Teschen, where he was later baptized on 27 January. Prior to Ullmann’s birth, his father, who was of Jewish heritage, had officially renounced his faith and converted to Catholicism in order to advance his military career as an officer in the Austrian army. In order to avoid the itinerate lifestyle that her husband’s work imposed on the family, when he was dispatched for extended periods to military outposts throughout Silesia, Ullmann’s mother moved with him to Vienna in 1909, where he attended gymnasium until 1916. Concurrent to his schoolwork, Ullmann studied piano under Eduard Steuermann and received theory and composition lessons from Arnold Schoenberg’s student Josef Polnauer, beginning in 1914. Although there is little documentation concerning Ullmann’s early musical engagements beyond these lessons, a program from his gymnasium years indicates that Ullmann conducted his school orchestra in 1915 in a concert of works by Mozart, Schubert, and Strauss.

After completing his Kriegsabitur, facilitating his early graduation from the gymnasium in May 1916, Ullmann enlisted for voluntary military service and was sent to the Isonzo–Front, after initially serving in a garrison in Vienna. Decorated for bravery for his service in the war, Ullmann was made a lieutenant in 1918. Returning to Vienna that year after two years of military duty, Ullmann not only entered Vienna University as a law student but was also accepted into Arnold Schoenberg’s Composition Seminar, where his classmates included, among others, Hanns Eisler and Josef Travinek. Resuming piano lessons with his former teacher Steuermann at that time, Ullmann, at Schoenberg’s recommendation, was made a founding member of the committee for the Verein für Musikalische Privataufführungen.

Professional Life in Prague: 1920–1927

In May 1919, after having worked with Schoenberg for less than a year, Ullmann married his fellow composition student Martha Koref, left the university and abruptly moved to Prague, where musical culture in this cosmopolitan European capital was centered around the Czech National and New German Theaters. Joining the staff at the New German Theater as a choir director and repetiteur in 1920, Ullmann underwent a rigorous training from its director Alexander Zemlinsky, who demanded that he develop a comprehensive grasp of both Czech and German musical repertories. In his capacity as choir director, Ullmann was responsible for preparing the choruses and soloists for different productions, which included, most notably, performances of Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder and Mozart’s Bastien und Bastiennein 1921. Appointed as a conductor at the theater in 1922, Ullmann maintained this position until 1927. During these formative years in Prague, Ullmann witnessed numerous performances of new works, including the Prague premiere of Berg’s Wozzeck at the Czech National Theater in 1926, which became the basis of his life–long admiration of the composer’s work.

Parallel to his activity at the New German Theater, Ullmann was composing new works such as the Sieben Lieder with piano (1923), the Octet (1924), his incidental music for Klabund’sKreidekreis (1925), the Symphonische Phantasie (1925), as well as the first version of his Variationen und Doppelfuge über ein Klavierstück von Arnold Schönberg (1925), based on the composer’s Op. 19, No. 4. An orchestrated version of this work later was awarded the prestigious Emil–Hertzka–Gedächtnispreisin 1934. Although composed in 1923, Ullmann’s First String Quartet, Op. 2, was premiered in 1927 on a program advertised as an “Evening of Prague Composers,” which included works by the composers Hans Krása, Karl Boleslav Jirák, and Fidelio Finke.

Ullmann was appointed as the conductor of the opera house in Aussig (now Ústí nad Labem) for the 1927 season, where he conducted, most notably, Tristan und Isolde, Ariadne auf Naxos, Le nozze di Figaro, and Jonny Spielt Auf. Returning to Prague at the end of that season, Ullmann remained without a permanent post, actively pursuing his career as freelance composer at that time. While his Concerto for Orchestra generated interest when performed in Prague in 1929 and in Frankfurt in 1930, it was the second version of his Schoenberg–Variationen, performed by pianist Franz Langer at the 1929 festival of the ISCM in Geneva, which brought Ullmann’s work to international attention.

Although the period between 1929 and 1931 can be seen as a highpoint of Ullmann’s career, when he was engaged by theZürich Schauspielhaus as a composer of incidental music and his works were being performed throughout Europe, it was also a time of spiritual and intellectual crisis. As part of facing his inner conflicts, Ullmann not only underwent psychoanalysis in Zürich but also continued his exploration of diverse esoteric paths of knowledge, including the I–Ching, the Freemasons, as well as the anthroposophy of the Austrian philosopher and scientist Rudolf Steiner (1865–1925). The term ‘anthroposophy,’ meaning ‘the wisdom of the human being,’ was chosen by Steiner to designate a path or epistemology for attaining occult knowledge that he developed through his engagement with Goetheanism, German idealist philosophy, esoteric Christianity, Rosicrucianism, as well the theosophical tradition. As a prominent intellectual figure in the cultural life of pre– and post–World War I Europe, Steiner lectured widely and developed a large following that included intellectuals, artists, scientists and politicians who drew on his ideas as a basis for their own work.

Ullmann and Anthroposophy 1929–1933

Although Ullmann “encountered” Steiner’s work through friends in 1919 while a student in Vienna, he initially rejected it. Ten years later at the time of his crisis in 1929, a visit to the Goetheanum—the international center of the anthroposophical movement in Dornach, Switzerland—became the basis for a radical reorientation of his worldview. Compelled by his new experiences, he eventually joined the Anthroposophical Society in 1931 and subsequently abandoned his musical career for a period of two years in order to manage, and later acquire, an anthroposophical bookstore in Stuttgart.

Despite the complete failure of this entrepreneurial endeavor, which, in his words, “led [him] back to music,” Ullmann’s sojourn in Germany between 1931 and 1933 was an important time of introspection. During this period, he developed friendships with Hans Büchenbacher and Herman Beckh, who were key figures in the German anthroposophical movement. Ullmann’s musical engagements within Stuttgart’s anthroposophical circles brought him into contact with the musicologist Erich Schwebsch, as well as with Felix Petyrek, a professor of music at the Stuttgart Academy of Music, whom he had known since secondary school in Vienna. As Ullmann explained it in a 1931 letter to his friend Alban Berg, he was reading “everything Steiner said […] about music” and working in Stuttgart at the Novalis Bookstore in order “to fulfill an old desire to serve the anthroposophical movement directly.”

Return to Prague 1933–1942

Following the rise of the National Socialists to power in Germany in 1933, Ullmann returned to Prague. As musicologist Ingo Schultz’ research has demonstrated, Ullmann’s sudden departure was not prompted by the fact that his Jewish identity had been exposed. Rather, it was due to the fact that a legal process had been initiated against him, because of debts he had accrued in conjunction with his eventual purchase of the Novalis bookstore. Arriving in Prague in July of that year and unable to secure a permanent position, Ullmann once again established himself as a freelance musician, making important contributions to both Czech and German musical culture there as a composer, conductor, music journalist and educator. As part of his professional activities, Ullmann lectured regularly at Leo Kestenberg’s Internationale Gesellschaft für Musikerziehung and additionally wrote articles and music reviews for journals such as Der Auftakt, Das Montagsblatt, as well as for Anbruch: Monatschrift für Moderne Musik.

Once in Prague, Ullmann began work on his monumental operaDer Sturz des Antichrist Op. 9, which he based on a drama of the same name by the anthroposophical writer Albert Steffen. (As a complex archetype of evil in the opera, the Antichrist brings unity to a world ravaged by perpetual war through the formation of a one–world state, which is imposed as the price of individual freedom.) In the opera, which essentially stages a battle between good and evil, the Artist–Poet— unlike the Priest and the Technician— is the only character able to harness the forces necessary to challenge the hegemony of the Antichrist. Completed in 1935, the opera was awarded the prestigious Emil–Herztka–Gedächtnispreis in 1936 by a jury that included Alexander Zemlinsky, Ernst Krenek, Egon Wellesz, Karl Rankl and Lothar Wallerstein, all of whom where leading figures in Prague’s cosmopolitan cultural life.

Despite the initial success of the work, however, it was never

performed during Ullmann’s lifetime. With the political movement to the

right in Czechoslovakia and Austria after 1933, the work’s

anti–totalitarian theme made it problematic for institutions like the

Vienna Opera and Czech National Theater that later considered it for

their repertories in 1935 and 1937.

Having completed Der Sturz des

Antichrist, Ullmann began a two–year composition course with Alois Hába

in his quarter–tone techniques (1935–1937), producing his Sonata für

Viertelton–Klarinette und Viertelton–Klavier, Op. 16 in 1936. Other

significant works composed and performed in Prague during this period

were his Piano Sonata No. 1, the Sechs Lieder for soprano and piano, Op.

17, with texts by Albert Steffen, as well as his String Quartet No. 2,

which was performed at the ISCM festival in London in 1938. Works

composed after 1938, including hisSlawische Rhapsodie, the Piano

Concerto, as well as his opera Der zerbrochene Krug, did not receive

public performances due to the political situation at that time.

Prague: 1938–1942

With the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in 1938, which effectively brought Czechoslovakia under German control, the political situation became increasingly dire as the Nuremburg Laws, which had been applied inside the German Reich, were then applied to the regions in Czechoslovakia under jurisdiction of the protectorate. As a result, the authorities of the occupation introduced anti–Jewish legislation through the puppet government of the protectorate, which, among many other measures, eventually expelled Jews from public life and institutions. After the invasion and subsequent defeat of Poland on 1 September 1939, the administration made plans for massive transports of the Jewish population to take place out of the occupied territories.

In this climate of escalating political tension and fear, Ullmann no longer attempted to have his Der Sturz des Antichrist staged. Rather, he directed his efforts towards procuring emigration visas for his family, which now included his second wife Annie Winternitz, whom he had married in 1931, their sons Max and Johannes, as well as their daughter Felicia. In a series of letters written to friends and colleagues in places as far away as South Africa, Ullmann appealed for help. By the end of 1939, having exhausted all possibilities for immigration, Ullmann and his wife made the decision to send their two oldest children Felicia and Johannes in a children’s transport to England through the British Committee for Children in Prague.

Although Ullmann continued to compose during this difficult period, even self–publishing several new works during the first two years of the war, his personal circumstances grew increasingly serious. With the finalization of his divorce from his second wife Annie in August of 1941, Ullmann, who was already stateless, became single, making him particularly vulnerable to the threat of deportation. By mid–October of 1941, it was known that the administration of the protectorate was making lists for five transports of approximately one–thousand stateless and single Jews from Prague to be deported to the Lodz Ghetto. In a desperate and last minute effort to prevent his anticipated deportation, Ullmann married his new partner Elisabeth Frank–Meissl on 15 October 1941. Although Ullmann did receive a deportation notice for Lodz, the Office of Jewish Community Affairs in Prague intervened on his behalf, providing him with a requisite identification card that effectively rescued him from the transport. This protection was temporary, however, and the following year, on 8 September 1942, Ullmann and his new wife Elisabeth were deported to Terezín, or Theresienstadt as it was renamed by the Nazis, a concentration and transit camp located north of Prague.

Terezín/Theresienstadt: 1942–1944

At Theresienstadt, under the auspices of the Freizeitgestaltung(the Administration of Leisure Activities), a cultural organ of the Jewish self–administration in the camp and officially sanctioned by the SS, Ullmann composed twenty–three works. These included three piano sonatas, a string quartet, arrangements of Jewish songs for chorus, incidental music for dramatic productions, his one–act opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis, as well as his final work, a melodrama based on Rilke’s Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke, which he completed in 1944.

Parallel to his activity as a composer in Theresienstadt, Ullmann was also influential there as a pianist, conductor, music critic and lecturer and additionally served as the director of the Studio für neue Musik. In that capacity, Ullmann championed the work of his fellow composers in the camp, including that of Pavel Haas, Hans Krasa, Gideon Klein, and Siegmund Schul, in particular. Ullmann’s twenty–six surviving reviews of musical events in Theresienstadt, which were a product of his ongoing activity as the official music critic in the camp, provide an important perspective on the astounding cultural life that developed there. Having begun underground, this cultural activity was later allowed to flourish openly, because it provided the Nazis with a propaganda vehicle to deceive the outside world about the conditions in Theresienstadt, which was portrayed to the Red Cross as a “model camp” during their decisive visit in June of 1944. Behind the façade created by the regime, however, the prisoners where subjected to the same hardships and brutalities as existed in the larger concentration camps, including disease, starvation, torture, executions and the frequent transports to the extermination camps in the east.

Death serves as both the historical and dramatic backdrop of Ullmann’s 1943 opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis, which he composed while a prisoner in Theresienstadt. Based on a libretto by the young Czech poet and painter Petr Kien, who was also active in the cultural life in the camp. Der Kaiser von Atlantis is a profound meditation on death that stages a dramatic confrontation between the Emperor of Atlantis and the character of Death. The central problem of the opera develops when the Emperor of Atlantis declares a holy war against evil elements in his empire and seeks “to conscript Death to his cause.” Insulted by the Emperor’s effort to involve him in his modernized military campaign, Death—who is already offended by the “mechanization of modern life and dying”—refuses to cooperate. Instead, he decides to teach the Emperor and humanity a lesson that will demonstrate his centrality in regulating existence by making it impossible for anyone to die.

Although Der Kaiser von Atlantis was composed and rehearsed under the auspices of the Administration of Leisure Activities in Theresienstadt, it was never performed in the camp. The parallel between the despotic character of the Emperor Overall and Hitler appears to have been obvious to the SS, who cancelled the production after observing a rehearsal in the autumn of 1944. As a critique of modern warfare and the political tyrannies that perpetuate war, Ullmann’s Der Kaiser von Atlantis—like Der Sturz des Antichrist—can be understood as powerful allegory on the despotic nature of power, where the dramatic confrontation with tyranny and death is portrayed as a powerful catalyst in shaping the exigencies of human freedom.

Ullmann’s Musical Language and Aesthetic

In a 1938 letter to his friend Karel Reiner, Ullmann reflected on the development of his musical language, making it clear that his earlier compositions, particularly his Variationen und Doppelfuge über ein Thema von Arnold Schönberg für Klavier, Op. 3a, had been shaped in terms of their harmonic and architectural conception by his engagement with Schoenberg’s teachings. Although Ullmann’s musical development falls into roughly three periods, with the first extending from 1920 to the early 1930’s, he had already begun to distance himself from the Schoenberg school by 1924 as he came increasingly under the influence of Berg’s work at that time.

Characteristic of Ullmann’s second period is his first piano sonata, composed upon his return to Prague in 1933. Ullmann termed this work one of his “new endeavors,” where “new harmonic functions within the framework of a tonality […] could be called polytonality. The principal tonality is three tonalities, but this is not essential. What is apparently happening is the linking of the twelve tonalities and their related minor keys.”

Acknowledging Berg as the first composer to bridge the historical–musical impasse precipitated by the crisis of tonality at the beginning of the twentieth century, Ullmann strove to further Berg’s path of synthesis between tonality and twelve–tone techniques. In his own work, Ullmann was striving for a musical language that would, as he explained it in the letter to Reiner, “serve as a twelve–tone system on a tonal basis [and be] similar to the merging of major and minor keys.”

The final stage of Ullmann’s musical development took place in Terezín, where the “formal and expressive mastery” he had achieved during his final years in Prague was harnessed to fulfill the demands of the musical culture in the camp. In an essay entitled “Goethe and Ghetto,” written during the final months of his life, Ullmann makes it clear that he confronted the desolate landscape of the concentration camp in spiritual and aesthetic terms. This compelled him to write “Theresienstadt was and is for me a school of form.” As he explained it, “earlier, when one did not feel the impact and burden of material life because comfort—this magic of civilization—suppressed it, it was easy to create beautiful forms. Yet, in Theresienstadt, where in daily life one has to overcome matter through form, where everything musical stands in direct contrast to the surroundings: here is true school for masters […]”

During the late summer of 1944, as news filtered into Theresienstadt that the allies had invaded Europe and the Russian front was drawing near, the prisoners waited eagerly to be liberated. From September to October, however, massive transports from Theresienstadt to the Auschwitz and other death camps in the east effectively liquidated the camp. Ullmann was sent to Auschwitz on 16 October 1944 where he perished two days later along with other key figures from the cultural life in the camp.

Zikmund Schul

Zikmund Schul was born to an assimilated Jewish family in Chemnitz, Germany, on 11 January 1916, moving with his parents to Kassel, in Saxony, on 3 September 1928. Zikmund and his father departed from Germany, taking residence in Prague on 7 October 1933. At some point, he studied with Paul Hindemith at the Berlin Musikhochschule, returning to Prague in 1937 and continuing composition with Fidelio Finke and conducting with George Szell at the German music academy. A work from this period was very well received by a critic who wrote:

The highly accomplished composer, a student of the master class—inspired, incidentally, by Hindemith—is Siegmund Schul; who, in his rich imagination presents an extremely interesting work for the string sextet which stands on its own feet in terms of theme and style. (German newspaper, 9 June 1937.)

At this time he attended a Kapellmeister class and attended lectures by Alois Hába. Still in 1937, Schul set Isolde Kurz’s poem, ‘Die Nicht-Gewesenen’, followed by a song-cycle, Gesänge an Gott, which was broadcast live.

Further Prague compositions, through summer 1941, included a piano sonata, of which only the final movement, a fugue, survived. A flute and piano sonata has not been found, nor a liturgical setting of the Mogen owaus Friday night prayer. During his Prague years, Zikmund became closer to his Judaism and was friendly with the Lieben family. Evidently Rabbi Lieben, of the Altneuschul, encouraged Schul to study Kabbala as well as synagogue songs. With the encouragement of Rabbi Lieben, the Jewish community offered him the opportunity to work with an early 19th-century collection of recitatives and chants for use in synagogues, which is now located in the Jewish Music Research Center at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in the National Library. During his years in Prague, he became friendly with Viktor Ullmann, who admired the work of the young man. Schul was transported to Terezín on 11 November 1941. During his imprisonment, he managed to continue composition and often met with Ullmann to discuss aspects of modern music.

The extent to which Schul selected Biblical texts for original compositions and arrangements, both instrumental and vocal, is quite remarkable. The Hebrew texts, selected from the Jewish liturgy, were clearly chosen to bolster hope rather than despair: ‘To build and to plant, to plow and to sow. And the wasteland will be worked and will no longer be desert’ (from Jeremiah, Isaiah, Samuel and Ezekiel). ‘Sound the great Shofar [ram’s horn] for our freedom…’ (When you come to the land). Several of Schul’s works in the ghetto included choral pieces, both original and arrangements. One of these works, written in summer 1941, Shield To Our Fathers, was scored for soprano, baritone, mixed choir and organ. It is not certain if it was performed.

Two of his Jewish instrumental pieces were on Ullmann’s second concert programme, ‘Young Composers in Terezín’, in his Studio für neue Musik series: Two Chassidic Dances for violin and cello and Divertimento Ebraica, written for Egon Ledeč’s string quartet. This work had evidently been admired when it was written and was then performed by the Ledeč-Quartett in 1942 and again in autumn 1943 at the above mentioned concert, and once more in mid-August 1944, this time as a memorial to Schul, who had suffered lengthily from tuberculosis and died in the camp on 2 June 1944. Although the quartet was ultimately lost, there was some critical evaluation. Ullmann wrote of it:

It is very clear that Schul turns, probably for the sake of tonality, to the variations of a Hebrew folksong (Divertimento Ebraico) in his Theresienstadt work for the string quartet. [Following its last performance he added] In the end it was supposedly Ledeč’s new quartet … in mind, which came up with a magically beautiful and excellently performed piece of Haydn for us, followed, finally, by Zikmund Schul’s interesting, well worked (and already well known) Divertimento Ebraico.

When Ullmann gathered Schul’s manuscripts together with his own as he was about to board the transport to Terezín, he was persuaded to entrust both his and Schul’s to the care of some friends who accompanied him to the train. Schul’s surviving works remained with Ullmann’s and many years later were deposited in the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland. In 1993 Schul’s collection was sent to Israel. After Schul’s death Viktor Ullmann wrote an article about Zikmund’s music, sharing something of their conversations:

In the last years he [Schul] liked to discuss all the problems of the new music, questions of form and tonality, their reshaping and breaking up, questions of style, aesthetic, the current view of the world and many details pertaining to some of his works in progress … was thus getting a rare insight into the artistic development of this personality whose true calling was music… I am not using the commonplace phrase of ‘In Memoriam’ when I maintain that he was fully justified in saying, just before he died: ‘What a pity I have come to this’… And it was the truth. (Viktor Ullmann, Theresienstadt, June 1944)

Schul, himself a violist, completed his Duo for Violin and Viola on 28 February 1943. Of his compositions written in Terezín that survived, the Duo is perhaps his major work. Unfortunately, the first 74 bars of the opening movement are missing from the manuscript. The remaining 60 bars, nearly half the movement, are retained.

By David Bloch

Recent Comments